Elon Musk’s Hyperloop Will Revolutionize Transportation, But That’s Only The Beginning Of The Change It’ll Bring

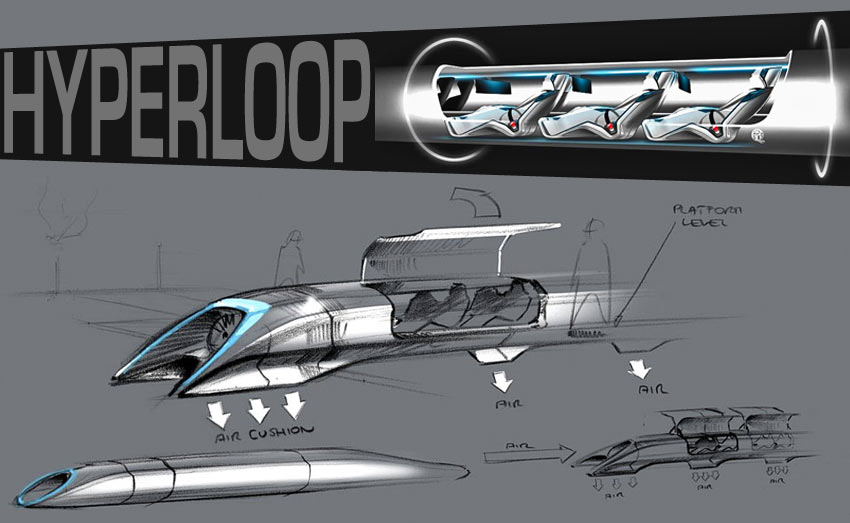

San Francisco to Los Angeles in 35 minutes flat—that was the dream of the Hyperloop.Back in 2013, Elon Musk introduced the world to this dream a 60 page white paper. The paper caused a stir. The idea—a levitating, solar-power supersonic train—was both pure geek porn and a transportation revolution in the making. It definitely captured people’s imagination.But would it ever get made—now that was the question.

Musk himself said he was too busy to take on the project, but if other people wanted in on the cause, well, that was just fine with him. As it turns out, other people have taken him up on his offer—about 100 in total.

Meet Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, (HTT) a company that is not quite a company.

Using JumpStartFund, a crowdfunding and crowdsourcing hybrid service/model, wherein the very workers who are going to build the Hyperloop aren’t paid until the train turns a profit.

How is that possible? Simple, the workers don’t actually work for HTT, or not many of them. Most of them work day jobs at companies spread throughout the country—Boeing or SpaceX or NASA or Yahoo! or Salesforce or Airbus, to name but a few. HTT is a company built on quasi-moonlighters, lending their cognitive surplus to supersonic train design. In technical parlance, they’re a mesh network.

Moreover, they’re a mesh network who had to apply for the job. This means that unlike most crowdfunding efforts, where you have to take what you get, this one got to pick and choose. Not only does this give them a much higher level of talent working on the project, it also gives them a pretty healthy reserve pool, should workers involved get sucked into other projects—which, since nobody’s getting paid for a while, is bound to happen.

And it could be quite a while.

A few weeks ago, the 100 or so engineers who make up the HTT mesh network got together to get going, penning a 76-page report on their plans, arguing they can complete their first Hyperloop (which, as it turns out, may link LA to Las Vegas, contrary to Musk’s originally proposed LA to San Francisco route) in about ten years for a cost of roughly $16 billion.

What strikes me as interesting here is the parallel between the new kind of organizational structure required to build a technology like the Hyperloop—the aforementioned mesh network—and the new kind of social structure the Hyperloop is going to ultimately create.

In macroscopic terms, distance is a brake on business. It comes down to the very human factor of trust. We all know that business requires trust to succeed and that the creation of trust—for reasons that have everything to do with evolutionary biology—requires interpersonal contact. Enter the Hyperloop.

A transportation technology that allows Angelinos to commute to job in Vegas or San Francisco or wherever it ends up, is going to make neighbors of literally distant strangers. Suddenly, people who live in different cities will eat lunch in the same restaurants. They’ll share cabs (arguably robo-driven cabs, but cabs none-the-less). They may go to the same gym. In this way, the Hyperloop will radically extend our interpersonal networks in ways we can’t begin to image and, by extension, reshape the ways we do business.

So on both ends of the spectrum—in the organization structure it takes to build the Hyperloop and in the organizational structures that will emerge once the Hyperloop is built—we’re looking at a revolution in business disguised as a revolution in transport.

Weiterführende Inhalte

| Getting Up to Speed! Two New Jets Plan to Take Air Passengers Supersonic Again |

| The son of Concorde is coming! |