Airliners have become steadily bigger in an effort to take fit in more passengers and drive down the cost of tickets. Could a new outsized design change the way we fly?

Spotting an Airbus A380 at an airport can still create great excitement. The giant, double-decker plane can seat between 500 and 850 people, depending on how much space is given to space-saving economy class, and how much goes to higher-paying passengers with all that extra leg room. It’s an aviation giant, the biggest passenger-carrying aircraft ever to fly the skies.

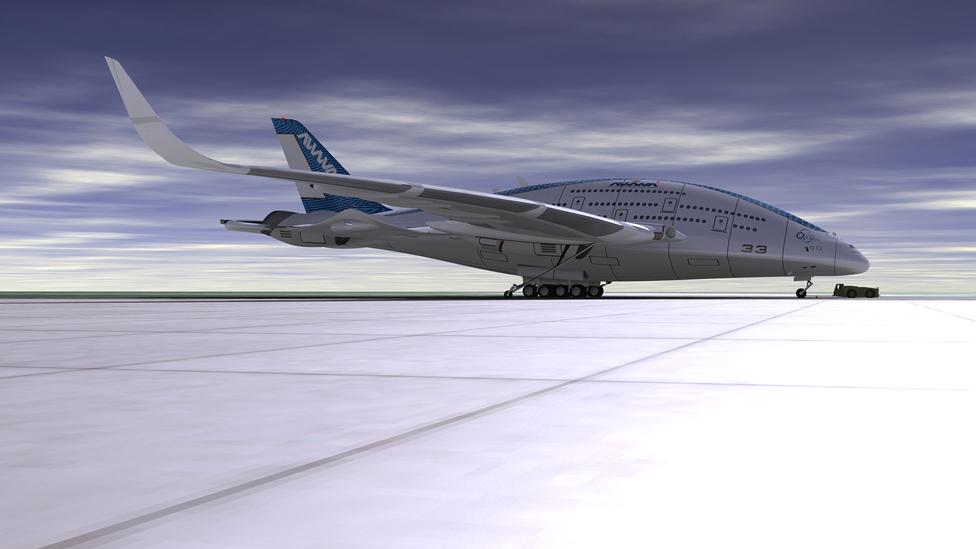

AWWA Sky Whale (Oscar Vinals)

But the A380 could be become small fry if another, even more outsized design takes to the skies.

The AWWA Sky Whale is a concept aircraft from Spanish designer Oscar Vinals. With three decks for passengers, it looks like a cross between a tropical fish and a sci-fi space shuttle. Does this huge design herald the future of air travel?

Bigger means better in the world of airliners; the dawn of the jet age brought in the likes of the Boeing 707, an aircraft capable of carrying more passengers quicker and faster than any propeller-driven design. In the ensuing decades, airliners have grown larger and larger. The advent of “jumbo” designs, characterised by Boeing’s 747, meant more passengers per flight, and therefore cheaper seats.

The plane would have swivelling engines for shorter take offs

“Travelling in the Sky Whale could be like a travelling in your private ‘theatre seat’, enjoying what happens around you; hearing some air flow noise, but feeling safe inside a big and intelligent structure,” Vinals says.

The design would use advanced technologies such as self-repairing wings, swiveling engines to enable a near vertical take-off, and hybrid propulsion.

“The engines and batteries are fed by a turbine inside the wings, like a high-speed and powerful dynamo,” says Vinals.

The design also calls for a system to redirect air flow to intake engines and to control laminar flow – in other words, to reduce turbulence around the plane and reduce drag.

None of these technologies are feasible on a large scale at the moment, but all are possible, says Vinals.

“I did this because I am an aerospace and aviation enthusiast – the technology, development and evolution,” he explains. “I would like to contribute, with my vision, about these.”

Perhaps that vision from someone outside the aerospace industry, without preconceptions, is what is needed to revolutionise plane design. Vinals told me he did “years” and “terabytes” of research. It’s an approach that some in the field appreciate.

“I think that’s where these concepts come in,” says Dr Michael Jump, lecturer in aerospace engineering at the University of Liverpool. “It’s people challenging through their imaginations. It’s the engineering community’s opportunity to either say ‘that’s a good idea, let’s try and make it happen’, or ‘it’s less of a good idea, and this is the reason why’”.

He says there are three factors to consider when evaluating the design of an aircraft, collectively known as the Breguet Range equation. This can be used as an estimate of efficiency.

The design would limit turbulence around the wings, thus decreasing drag

They are: propulsive efficiency (how efficient are your engines?); aerodynamic efficiency (is lift maximised and drag minimised?); and structural efficiency (how much payload can you carry?).

Generally airlines want to fly as far as possible, with the biggest load (or largest combined weight of passengers) possible, while using as little fuel as possible. If you can maximise all three, you technically have a better aircraft design. The major airliner manufacturers have made tweaks to this equation, but have largely stayed faithful to a tried-and-trusted design.

“The likes of Boeing and Airbus have a lot of experience of building aircraft that look like a tube and two wings,” says Jump.

“When it comes to a new airframe that they want to design, it makes sense to evolve rather than revolutionise.”

A cylinder is also a structurally efficient way to contain pressure, which aircraft must do to maintain the right air pressure for passengers when flying at high altitude.

The Airbus A380 (left) is currently the biggest airliner in the world

Mark Drela, professor in the department of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT, agrees. “The airplane fuselage is a pressure vessel,” he says. “It really needs a circular cross section for that. You don’t see scuba diving tanks that are rectangular. If it’s round, then it’s light.” On a plane, of course, weight is everything.

“Airplanes look the way they do, not because of some stylistic decision, but almost entirely for technical reasons,” he says. “Form follows function.”

For that reason, Drela doubts the usefulness of design exercises like this one. “It’s more of a stylistic concept,” he says.

What’s more, for a manufacturer to be able to sell a new aircraft, it has to demonstrate that it is safe. The safety regulations have evolved over a century of manned flight, but with a radical design it would be much harder to demonstrate safety.

“The optimised airplane is like a grand set of compromises, and it’s a colossal exercise to balance everything,” says Drela.

“Airbus went with the huge A380, Boeing put its money on the smaller airplane with 787. And it is not obvious which is the better approach yet.”

But, Vinals says, Albert Einstein might have the last word on this: “Your imagination is your preview of life’s coming attractions”.