As cities get more crowded, why not build down? Kieran Nash profiles some of the world’s most unusual underground constructions, from Australian rock homes to Beijing’s subterranean spaces.

A running track underneath Helsinki in Finland (Credit: City of Helsinki)

In many respects, Bernadette Roberts’ three-bedroom house is like any other. “Lounge, dining area, kitchen – it’s got all the mod cons. It’s like a normal home.”

Only it’s not a normal home – Roberts lives underground. She’s a resident of Coober Pedy, a tiny town 846km north of Adelaide, South Australia, that is known for two things: its opal mines, and its “dugouts” – subterranean homes carved from the rock, which house 80% of the town’s population.

Coober Pedy is an inhospitable place, where temperatures can reach 50C. A century ago, miners realised it was much cooler to live beneath ground, and the town’s residents have stayed there ever since.

A subterranean bedroom in Coober Pedy (Credit: Torsten Blackwood/AFP/Getty)

Roberts says “on a good day”, when temperatures outside are in the high 30s or low 40s, the temperature in her dugout is around 23 to 25C. “It’s like you’ve walked into an air-conditioned room.”

While extreme weather has forced Coober Pedy’s residents underground, it’s not the only place on Earth where authorities are looking beneath the surface for new urban space.

With two-thirds of the world’s population expected to live in cities by 2050, urban land is expected to become an increasingly limited resource. Many cities – due to space constraints, heritage areas, or other factors – cannot build up, or out. But what about down?

An underground church in the opal mining town of Coober Pedy in Australia (Credit:Quinn Rooney/Getty)

Consider the case of Singapore, one of the most crowded countries on the planet. Its population of nearly 5.5 million people is squeezed into a city state that covers just 710 sq km. “For Singapore, the main thrust for going underground is really to solve the land shortage issue,” says Singapore-based Zhou Yingxin of the Associated Research Centers for the Urban Underground Space, a non-governmental organisation of experts who design and analyse cities' subterranean spaces.

“Traditionally, we’ve tried to reclaim land by digging up the sea and buying sand, but that is becoming less and less viable – the sea is getting deeper, we’re getting to the boundaries, the sand is getting more expensive, our neighbours are complaining and all that.”

So, one plan currently on the table is an Underground Science City(USC). Designed to house a 300,000 sq m research and development facility 30-80m below the surface, the USC will support biomedical and biochemistry industries, among others. If completed, it is estimated to house a working population of 4,200.

A design for Singapore’s Underground Science City (Credit: JTC Corporation)

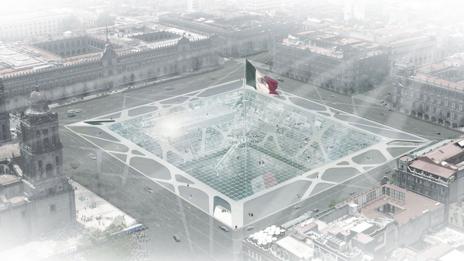

In other cases, land is scarce because of heritage restraints. In Mexico City, for instance, there are strict building restrictions in its historic centre. That’s why architecture firm BNKR Arquitectura has designed a massive, 300m-deep inverted pyramid dubbed the Earthscraper.

The proposed building would house 5,000 people, with terraced floors receiving natural light from a huge glass ceiling above – although the lower floors will need extra lighting with fibre optics.

BNKR founding partner and CEO Esteban Suarez hopes the Earthscraper will inspire a new “species” of building.

The proposed Earthscraper in Mexico City (Credit: BNKR Arquitectura)

Meanwhile, in China, demand for affordable housing in Beijing is forcing people to move below the surface in less glamorous conditions.

Annette Kim, director of the University of Southern California’s Spatial Analysis Lab, spent almost a year in China’s capital from 2013 to 2014 studying the conditions for those living in the city’s underground housing – a mixture of former bomb shelters and common basements repurposed to act as small dorm room units.

“There’s a big range in housing conditions. I envisioned horrible squalor – and there are places that are terrible – but what was surprising is there were also places there that were really nice, relative to Beijing standards.”

Millions

So how many people live underground in Beijing? Kim says official estimates vary between 150,000 and two million. “As a shorthand, I just say one million. It’s pretty incredible.”

Kim says that two factors have led to this situation – China’s huge building boom, which has created an increased supply of underground space, and a shortage of affordable housing. In recent years, a huge number of rural workers looking for better jobs have come to Beijing, but many do not have an official residency permit, making them ineligible for the housing available to Beijingers above ground. The only flats they can afford are subterranean spaces offered in the expensive private housing market.

The Shimao Wonderland Intercontinental hotel, in Songjiang, Shanghai (Credit: Atkins)

About 1,000km south of Beijing, developers are exploring a totally different use of underground space with the Shimao Wonderland Intercontinental – a 300-bedroom hotel currently being built into the rock face of a disused, 90m-deep quarry 35km south-west of Shanghai.

Martin Jochman, a design director responsible for the hotel’s concept and scheme design, says that while the quarry makes for an attractive landscape, many people thought it unusable.

“It’s extremely difficult because everything is upside down. Things like water and sewage have to be pumped up rather than going down. It’s like a building that goes down rather than up.”

But there are benefits. The topography of the quarry creates a microclimate – the rock draws in heat over summer, slowly releasing it like a storage radiator in winter.

Helsinki’s underground Hartwaal Arena (Credit: City of Helsinki)

Temperature is also a factor in Helsinki, Finland, where authorities have built nine million cubic metres of facilities under the city – including shops, a running track, ice-hockey rink and swimming pool.

Lead designer of the city’s underground master plan, Eija Kivilaakso, says conditions underground are often more favourable than those above, especially in winter, when surface temperatures can drop below -20C.

“With the weather in Helsinki, it’s nice to work or get coffee underground – we don’t have to go out in the rain or the cold.”

Dark fears

It’s technically possible to build underground living spaces for people. But are we willing to spend long periods of time in subterranean dwellings? The success of building proposals like Mexico City’s Earthscraper might depend on helping people overcome fears associated with the underground.

“The human mind is naturally predisposed to fear underground spaces, which it associates with dark, small, cavernous environments and a danger of being buried alive,” says Suarez.

But by connecting all areas of the Earthscraper to a large, central, open space that receives light from above, Suarez hopes to change people’s perception of the underground – he likens it to an open canyon.

The Earthscraper has been designed so that people don't feel claustrophobic (Credit: BNKR Architectura)

For a small percentage of people, the mere thought of being underground in a confined space can be terrifying. Gunnar D Jenssen, who researches underground psychology and space design for Scandinavian research organisation SINTEF has found about 3% of people are severely claustrophobic – not having a clear way out or being fearful of flooding or fires can cause a lot of stress. But there are some way to counter their fears.

“If you give these people something that gives them perceived control over the situation, they accept being in it. That is the key. Transferring that into architecture, into design is the line of work we’ve been following.

“The basic things you have to have there is clean air, you have to have the space, it has to be spacious or perceived [to be] spacious. You can use illusions but the best is if it really is spacious and [has] good lighting.”

Jenssen has worked on four of the longest road tunnels in the world. To create the illusion of space, within the tunnel he creates well-lit oases with palm trees and illusions of the sky along the route. “You go through a dark tunnel and all of a sudden you’re coming out into a bright lit space with trees and plants.

“You have a feeling of breathing space, a feeling of being outside, even though you’re 1,000 metres underground going through a mountain.”

A design for New York City's Lowline, an underground park (Credit: Raad studio)

Using illusions and design tricks to make ourselves more comfortable underground is one thing, but if we were to live underground, would we suffer adverse effects from a lack of sunlight?

Lawrence Palinkas, from the University of Southern California, says a lack of sunlight can cause difficulty with sleep, mood and hormone function which can produce chronic diseases of different varieties. But, “timing and routine exposure to bright light that can mimic the properties of sunlight might enable people to live underground for long periods of time”.

Temporary abode

So, technically, we can live underground. But will we? Annette Kim, having seen first-hand the effects of Beijing’s housing demands, thinks we might. “If we continue to have this rapid urbanisation and people want to come to the big cities, we’re going to have to, yes.”

She says it also depends on how the space is used: “A lot of these people are going there to sleep at night. It’s not as if it’s my ‘home sweet home’ to hang out in – they enjoy the public spaces above ground to be in the sunlight and air.”

Li Huanqing, a research fellow at Nanyang Technological University who made underground urbanisation the focus of her doctoral thesis, says most cities are not planning underground houses, but multifunctional underground spaces that will be occupied by shopping malls and public thoroughfares to free up more surface land for housing, green space and recreation.

Zhou says this makes sense. “There’s no reason why people cannot live underground,” he says, but “there are a lot of things you can put underground first”.

http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20150421-will-we-ever-live-underground